How a Formal Network Design Capability Can Help Medical Products Manufacturers Thrive (2 of 4)

July 22, 2016 By: Senior Management | Topics: Facility & Operation Design, Healthcare, Network StrategyThe Case for a Formal Network Design Capability

This series explores the overarching trends that are upending the healthcare supply chain; why a formal network design capability is becoming essential to medical products manufacturers’ competitiveness and growth; and how manufacturers can develop such a strategic capability to position themselves for success.

In Part 1 of this series, we identified the three major trends that commonly unfold in healthcare supply chains and can disrupt medical products manufacturers’ supply chains, forcing a costly readjustment or, in some cases, a complete redesign. In this post we detail the strategic activities involved in managing and executing network design on an ongoing basis.

Part 2

Managing and executing network design on an ongoing basis requires a formal organizational capability. In fact, the ongoing upheaval in healthcare is making such a capability a competitive necessity for medical products manufacturers.

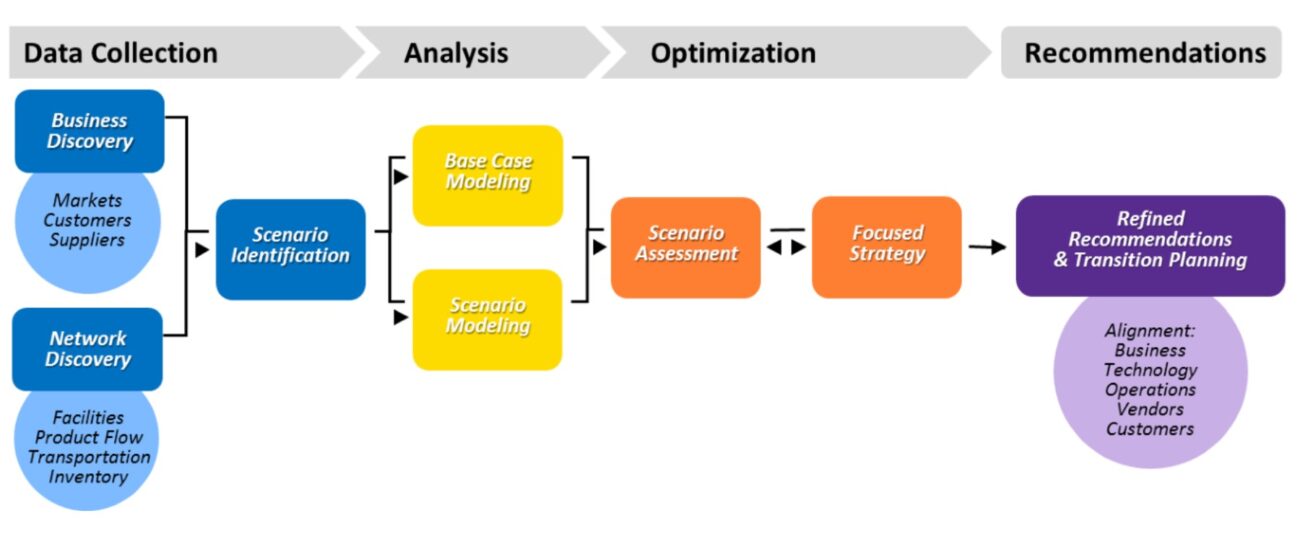

What does such a capability look like? At its core is a strategic and repeatable process, the essential elements and flow of which are illustrated above.

Data Collection

The process begins with collecting the data required to forge a deep understanding of the company’s existing supply chain network. This takes two forms. In business discovery, a company looks to gain clarity on higher-level issues—such as the markets it serves, the types of customers it sells to, and key competitors it must fight for business. In network discovery, the focus is more tactical, concerned with such things as product flow and transportation costs. Combined, business and network discovery give a company insight into key dimensions of its supply chain:

- Current state of its assets: (e.g., rolling stock) and brick-and-mortar facilities (both company-owned and contracted)

- Capacity of existing facilities (often a driving factor for a network design initiative)

- Operations and process (how things work inside the company’s assets and facilities)

- Overall performance of the network (including costs and service levels)

Collecting such data is typically the most time-consuming step in the entire process. But it’s also the most critical, as it lays the foundation for fact-based decisions about the optimal network design.

Scenario identification and development accompanies discovery activities. During this exercise, a company discusses exactly what it will investigate from a network design perspective. For instance, a company that has grown through acquisition and has several more deals on the horizon needs to confirm whether the future acquisitions’ facilities should be included in the design. Or, a company with only half of its facilities certified to distribute a particular product must decide if the design should assume the rest will eventually become certified. Such conversations are critical to have at the outset of the process. They help define the scope of the effort which, in turn, ensures the right data is collected. In short, understanding the desired end state helps ensure efficient and effective modeling efforts.

Data Analysis

Once a company collects the relevant data, it’s time for modeling and validation to ensure the data reflects reality—in other words, that the data is as complete and accurate as possible. This “sanity check” is critical to avoid misrepresenting the existing network environment. For example, in one network design effort, a manufacturer inadvertently excluded an entire hospital system from the data collection effort—a fact that only became apparent once it modeled the data. In another, a company was surprised to discover that what it assumed to be its network-wide costs turned out to be significantly lower than the actual costs uncovered when regional cost data was aggregated.

The output of this initial modeling is the base case – the existing network environment. With the base case established, a company can then begin to create possible scenarios to illustrate the resulting impact on network design. By adjusting various constraints—including level and type of demand, desired average cost, geographic location of customers, capacity, and service requirements—the company can determine which types and sizes of facilities it would need, and where, to deliver the best business results.

Optimization

After a company develops a number of prospective scenarios, a handful will typically rise to the top as the most potentially desirable—the “finalists.” The company further vets these finalists through additional analysis, eventually determining the one that will best help the company achieve its business goals.

This is a critical exercise, as choosing the scenario to eventually implement is a major strategic decision that can have a massive impact on the business. It’s also an iterative process. In some cases, it becomes obvious very quickly which scenario is the best option. But more often than not, a company will require a fair amount of discussion, debate, and adjustments to the scenarios to arrive at “the answer.”

Recommendations

In the final step of the process, the company further refines the chosen scenario to ensure it aligns with the overall business and its technology, operations, vendors and customers. Key elements of this exercise include reviewing transition planning and organization alignment (to understand what exactly is involved in moving from the current to future state), sensitivity analysis (to determine how the move may impact other dimensions of the business), and risk analyses (to highlight how the new network design changes the company’s risk posture). Addressing these factors enables the company to shape the final recommendation for implementation of the new design.

While the process is the foundation of a formal network design capability, two other elements are vital to making it work.

Tools are needed to model the data. Historically, spreadsheets have been used most often, but their functionality is limited because they don’t support the creation and manipulation of sophisticated models. That’s why more robust analytical tools—whether custom-developed or packaged—are critical to the kind of advanced and complex network design today’s medical supply chains require. Spreadsheets simply are not sufficient or efficient to examine thousands or millions of potential options.

The second element is people: those who actually work on network design efforts. A company must determine which resources should be involved—for instance, an existing operational team or a dedicated analytical resource who may work in marketing, operations, or distribution. It also must identify the specific skills those people need to actually do the work—whether those skills already exist in the company or must be brought in from the outside.

The process of implementing a formal supply chain network design capability provides medical products manufacturers with options regarding how to acquire such a capability. In the next post, we will explore the options available to acquire a robust network design capability.

Sedlak has been helping healthcare companies improve operations and optimize their supply chains since the 1960s. To learn more, contact us by filling out the form below.