Found Money: How to Clean Up Preference Cards to Cut Inventory Spend (1 of 3)

August 12, 2016 Topics: HealthcareThis three-part series examines the potential for hospitals to capture savings through more efficient management of physician preference cards.

Part 1

Heightened cost pressures continue to force hospitals to look for ways to reduce wasted spend. In fact, in a recent survey, hospital executives said finding cost savings to meet their current-year objectives is one of their top challenges.

The supply chain—more specifically, inventory and order management processes—is a natural place to look for savings. A study from the International Journal of Supply Chain Management shows that inventory and order management costs account for 61 percent of total supply chain costs (or $61 million per year for a typical large healthcare provider).

The supply chain—more specifically, inventory and order management processes—is a natural place to look for savings. A study from the International Journal of Supply Chain Management shows that inventory and order management costs account for 61 percent of total supply chain costs (or $61 million per year for a typical large healthcare provider).

Charles Poirier, author of Diagnosing Greatness: Ten Traits of the Best Supply Chains, provides a compelling synopsis of the enormity of the opportunity. In a blog post, he estimated the $3 trillion U.S. healthcare system could cut $60 billion in inventory spend and $6 billion in working capital through better supply chain practices. As Poirier notes, “That is a lot of new free cash flow.”

Arguably the biggest driver of over-budget inventory spend are medical-surgical supplies—the disposable or implantable items used in the operating room that include high-cost physician preference items. These items, which can account for 30 percent to 40 percent of a hospital’s supply expenses, represent by far the largest percentage of inventory spend. That’s not surprising given the high cost of many items in the category. But they also are responsible for a substantial portion of the typical hospital’s inventory budget overrun. That was the case at one hospital, whose per-case supply costs exceeded the median cost for peer organizations by $300.

The Chief Culprit

Why do hospitals struggle so much to contain their medical-surgical inventory spend? The biggest culprit is the physician preference card.

The preference card specifies the supplies a surgeon requires to complete a particular procedure in the OR. It’s critical to ensuring the nurse pulls the right supplies from stock and has them at the ready when the surgeon needs them. The problem is, in a typical hospital, preference cards are often outdated or otherwise inaccurate.

Of course, preference cards were accurate when nurses created them. But over time, as surgeons change how they execute a procedure or learn about new products, nurses add items to the card—but often don’t remove the ones no longer used. In other words, they’re not spending time tweaking and refining preference cards. And that’s understandable: Nurses’ primary role is caring for patients. They’re not materials managers or inventory specialists, and when forced to choose how to juggle demands for their time, the patient always wins.

Yet the end result remains: Preference cards have come to resemble more of a laundry list of all items a nurse thinks a surgeon might require—rather than a reflection of a surgeon’s exact supply needs for a given procedure.

These inaccurate preference cards lead to substantial supply waste in the OR. For example, at one hospital, surgeons typically use only about 60 percent of the supplies pulled for a typical procedure. The rest are either discarded because the package has been opened and the remaining items are no longer sterile; or, if not opened or used, must be manually returned to stock. This helps explain why, according to one estimate, every year more than $5 billion is wasted on expired, lost or uncaptured medical device and implantable charges.

And returning items to stock can be very labor intensive. A nurse must reenter each returned item into the OR information technology system, deduct the charges to the patient and physically put the item back on the shelves. In isolation, the labor involved in returns for one procedure doesn’t seem like much. But in a large hospital that does 200 surgeries a day, and each surgery’s preference card includes 100 to 200 items and the OR and storeroom are two floors apart, it adds up quickly. Indeed, 70 percent of respondents in a recent survey said excess clinical time spent on inventory replenishment is a “very” or “somewhat significant” challenge to their hospital’s operating room.

But inaccurate preference cards don’t just lead to excess items being pulled for the OR. They also can mean an item the surgeon needs is not on hand when needed, requiring the nurse to quickly retrieve the product from the stockroom in the middle of a procedure. That’s not ideal for anyone involved.

Making matters worse, inaccurate preference cards have a major ripple effect on procurement. When nurses pick supplies for surgeries, the hospital’s broader inventory system considers them allocated or used. That tells procurement it’s time to order replacements for those items. But at the same time, procurement has no idea what might be returned to stock after the surgeries. Undoubtedly, some items will be returned, which means the hospital now has redundant supplies of those items—and those supplies will only continue to grow as the practice is repeated.

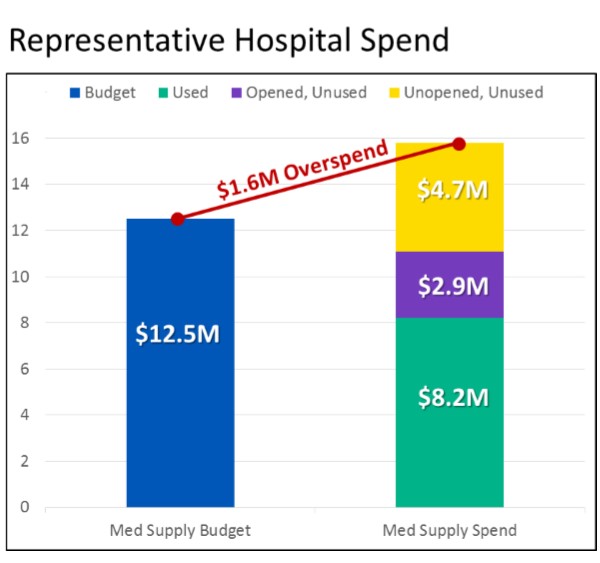

Such inefficiencies, waste and duplication can have an insidious effect on a hospital’s bottom line. Consider this typical scenario, which we developed based on aggregate data from five different hospitals. This analysis clearly illustrates how much inaccurate preference cards truly cost a typical hospital.

The representative hospital has an overall medical supplies budget of $12.5 million and conducts 22,000 surgeries annually. With the cost of an average preference card topping out at $1,200, that translates into $15.8 million a year spent on medical-surgical supplies. Of that, $2.9 million is spent on items that are opened and unused, and $4.7 million on items unused and unopened (222,000 of them annually). This adds up to $1.6 million in overspend a year based on perpetual inventory inaccuracies traced to outdated preference cards.

In the next section of the series, we will outline the actions hospitals should take to identify their losses and capture the potential savings available by cleaning up their existing preference cards.

Read the next post in this series.

Sedlak Management Consultants is an industry leader in supply chain strategy and inventory planning, with a specialize practice in healthcare. From manufacturers to distributors to providers, we help position healthcare companies to manage continual changes brought on by regulation, mergers and acquisitions, and ever-changing product mixes.

If there is any way we can support your healthcare supply chain or distribution efficiencies, please feel free to contact us by filling out the form below.